Microsoft has developed AMSI to detect malicious content to be launched by Powershell. The AMSI.dll is injected to the process memory after which the Antivirus programs can use the API to scan the content before it is being launched. If the content is malicious the execution will be prevented. This function works with Defender antivirus and many of the other antivirus’s are also detecting this function. There is an awesome list of different AMSI bypasses written by the Pentest Laboratories: https://pentestlaboratories.com/2021/05/17/amsi-bypass-methods/ - I am using this article to test out the bypasses. Some of the bypasses do not work anymore at least without tinkering so I will be targeting some of those that are working out of the box.

Powershell version 2 downgrade

The easiest way that I know of to bypass the AMSI would be downgrading to Powershell version 2. This is simple to do and there is a great MDE query for detecting this already in the Microsoft Sentinel and Microsoft 365 Defender repository, here. The repository has a plethora of very good and realistic queries to get hunting. Great place to look for queries and to check if your latest idea has already been covered there. I have been testing this before and the query works nicely and is not relying upon the commandline, which in my opinion is how it should be done.

Forcing an error

Forcing an error which is shown as the fifth option in the Pentest Laboratories article works fine. Forcing an error is still allowing to bypass the AMSI from the code that is launched after. Unfortunately, this seems to hide the activity from the Defender for endpoint console very well. So well that there isn’t really anything to look for. This can be seen from the Powershell logs though, if those are being sent to a SIEM.

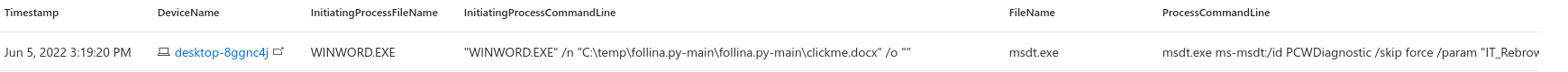

Powershell logs showing the bypass.

Powershell logs showing the bypass.

The other described bypasses were blocked, obfuscated or not under the Forcing an error method. Also, many if not all the others that I found and tested where already blocked, but I did not look into the topic very intensively. I wanted to have at least a single functioning test to verify what I can actually see from the activity after the AMSI bypass had been initiated.

Hunting for the AMSI bypasses

Generally, it seems that hunting for the actual AMSI bypasses seems to be relatively hard using only the MDE data. The registry based bypass should be easily doable, however because of the noise that it causes it is probably just not used in the wild. So maybe the hunting should be done against the actual behavior of the Powershell process. This is likely quite hard to do, unless pinpointing to very specific things. I try to not rely upon detecting something super specific like the cmdlets of the attack frameworks, rather I always try to think “step further” - catching the actual behavior instead of the indicators that might change.

I created a query which is looking for powershell.exe connecting to public address and then joining the data to the recorded commands ran by MDE. Then, this data is further joined to the child processes of the same Powershell process. This has not been tested live and I think it will cause too much noise, however here goes:

DeviceNetworkEvents

| where InitiatingProcessParentFileName != @"SenseIR.exe"

| where ActionType == 'ConnectionSuccess'

| where InitiatingProcessFileName has_any ("pwsh.exe","powershell.exe")

| where RemoteUrl !contains "winatp-gw"

| where RemoteIPType == "Public"

| project Timestamp, DeviceName,NetConTimestamp = Timestamp, RemoteIP, RemoteUrl, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCreationTime, InitiatingProcessId, InitiatingProcessParentFileName

| join kind= leftouter(

DeviceEvents

| where ActionType == 'PowerShellCommand'

| project PsCommandTimestamp = Timestamp, DeviceName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCreationTime, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessId, AdditionalFields, PSCommand=extractjson("$.Command", AdditionalFields, typeof(string))

) on InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCreationTime, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessId, DeviceName

| join kind=leftouter(

DeviceProcessEvents

| project ChildProcessStartTime = Timestamp, ChildProcessName = FileName, ChildProcessSHA1 = SHA1, ChildProcessCommandline = ProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCreationTime, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessId, DeviceName

) on InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessCreationTime, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessId, DeviceName

| project DeviceName, NetConTimestamp, RemoteIP, RemoteUrl,InitiatingProcessParentFileName,InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine, PsCommandTimestamp, PSCommand, ChildProcessStartTime, ChildProcessName, ChildProcessSHA1, ChildProcessCommandline

Usability is quite dependent on the environment, however this should show if Powershell is used to connect to the internet and then some suspicious commands are ran. For example, using IEX (Invoke-Expression) after AMSI bypass might get caught if looking at the data produced by the query. Here is an example of the data from my tests:

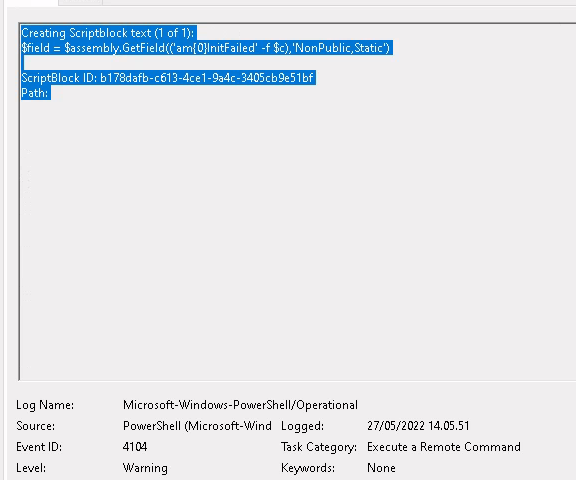

Example output of the query.

Example output of the query.

There are many other anomalous things which could be hunted for. Another example which is a little lame, is if Powershell is used to create an .exe file. Then, the data is joined to a process launching the binary file which was created by Powershell. This is not hugely relevant as the threat actors are relatively rarely using Powershell to download additional binaries that are then launched, more commonly the actual malicious deed is done by using Powershell code. This makes the use case for the query little niche, but maybe these can food for thought; try to think of how the threat actors are actually using Powershell and how that could be found by looking into the Powershell behavior.

DeviceFileEvents

| where InitiatingProcessParentFileName != @"SenseIR.exe"

| where InitiatingProcessFileName has_any ("pwsh.exe","powershell.exe")

| where ActionType == 'FileCreated'

| where FileName endswith ".exe"

| project Timestamp, FileCreationTimestamp = Timestamp, InitiatingProcessFileName, InitiatingProcessCommandLine, InitiatingProcessParentFileName, SHA1, FileName, DeviceName

| join (

DeviceProcessEvents

| project DeviceName, SHA1, FileName, ProcessCreationTimestamp = Timestamp, ProcessCommandLine, FolderPath, ProcessCreationParentName = InitiatingProcessFileName, ProcessCreationParentCmdline = InitiatingProcessCommandLine, ProcessCreationParentFolderPath = InitiatingProcessFolderPath, ProcessCreationGrandParentName = InitiatingProcessParentFileName

) on FileName, SHA1, DeviceName

| project DeviceName, FileCreationTimestamp, FileName, SHA1, ProcessCreationTimestamp, FolderPath, ProcessCommandLine, ProcessCreationParentName, ProcessCreationParentCmdline, ProcessCreationParentFolderPath, ProcessCreationGrandParentName

The following picture shows the results, however they are before making exclusion for the SenseIR.exe process. I got no hits without the filter, as I didn’t run any test to verify the functionality.

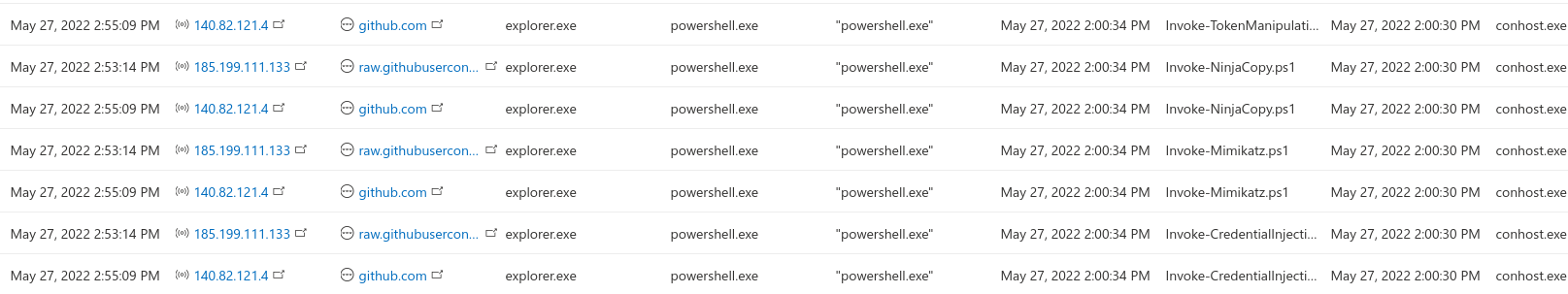

Results of the query when not filtering out SenseIR.exe.

Results of the query when not filtering out SenseIR.exe.

I would like to hunt for the actual AMSI bypasses as it would be much more pinpointed than trying to catch malicious behavior of the Powershell process. I am sure that some of the AMSI bypass techniques are catch-able with the MDE data, however I didn’t want to go through analyzing them all. This is more or less a relatively quick analysis of the known AMSI bypasses to see what works, what does not and what is detectable currently. Most of the bypasses that I came upon were already blocked, so they are nothing to worry about.

Maybe more interesting angle would be to create rules to catch Defender AV bypasses, however I think that they might be already alerted by MDE so that might not be really needed.

Bzz.. Bzz.. Bumblebee loader

Bzz.. Bzz.. Bumblebee loader