I haven’t observed any interesting new techniques recently, which is why I decided to analyze something that has been around for some time now. I’ve been interested in AsyncRAT for a while and decided to analyze it closer with threat hunting in mind.

AsyncRAT is a Remote Access Tool which has been according to the Github page designed to remotely monitor and control other computers through a secure encrypted connection. It is quite often used by the threat actors as it has many built-in features that are very useful for them. The tool allows the remote management but also includes things like SFTP, anti analysis features, keylogger, dynamic DNS server support and many other helpful features. Not sure how often some of the offered features would offer a legitimate use though.

Running the too.. malw.. whatever

The compiled binary is available in the GitHub repo, but I rather acquired a real malicious sample of the tool where it will connect to a command server. Thus, I browsed to tria.ge to see if there are any recent samples reported there. As per usual, there was plenty to choose from. My only requirement was pretty much that it would be fairly recent as a recent sample would most likely work. I decided to download a sample which also contained a loader called SmokeLoader, according to the tria.ge analysis. This is a fairly old loader which has been around since 2011, according to Mitre. The sample itself is a simple binary file. This resulted in a cmd-like window when it was ran - which was left running.

The data shows that the process proceeds to make an exclusion for the Defender Antivirus by running the following command: ““C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe” Add-MpPreference -ExclusionPath “C:\tmp\230106-aztefsdg69_pw_infected\SOA.exe” -Force”. It also launches .NET framework related binaries, a few of them. As the AsyncRAT is C# code it was pretty much expected.

This results in a process called “AddInProcess32.exe” in connecting to Telegram API address, api.telegram.org. Looking at the computer itself the process is still running after 20 minutes of the initiated connection to Telegram. It is likely waiting for the threat actor to get active and continue to do manual activity on the device. It seems that the malware didn’t too much (any) discovery, which is quite abnormal as most of the loaders run discovery commands and send the information to the C2 server straight away when launched. Out of the blue, 20 minutes after idling the “AddInProcess32.exe” accessed lsass.exe. This is often done by malicious processes to access the lsass memory to dump the credentials, but not sure if this is related to anything really this time.

I downloaded the AsyncRAT from GitHub, launched it and compiled a client for it. The first version which I compiled crashed straight away but the second sample that I created worked. This turned out to be quite boring as the client only loaded the .NET framework related DLL images after which it connected to the “Command Server”. There are similarities to the malicious sample but only in loading the DLL:s, which is pretty much to be expected from the binary.

A second sample

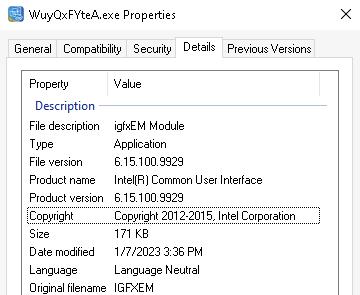

Just to verify the findings, I ran a secondary sample of AsyncRAT, to verify if there is some sort of pattern. Refreshingly, the second sample had at least a recognizable icon attached to it, the Intel logo!

Otherwise I noted nothing special of the binary, thus I launched it. This time it left no window behind so it is at least partly different. It loaded the same .NET related image files (mscoree.dll, cld.dll, mscorlib.ni.dll and clrjit.dll) which were loaded by the client retrieved from GitHub.

It seems that this is more or less the basic AsyncRAT client. The DNS query is sent to domain bevdona[.]theworkpc.com. Any further activity would most likely need for the threat actor to launch manual activity using the AsyncRAT server. I am not going to wait for the threat actor to get active this time although it could tell a little more of how the actual AsyncRAT works.

Not sure what I was expecting especially as the second sample was reported of being indeed a sample of AsyncRAT - the first one was likely a bit more customized as it came bundled with the SmokeLoader. There isn’t a huge amount of possibilities for conducting a threat hunt against the actual AsyncRAT. The hunting part is explored next.

Threat hunting

For starters, I added the Sysmon and some other log data to Sentinel. I like KQL a lot which is why I added Sysmon data also to KQL - it does still flow to Splunk too. KQL makes my life easier as I am much better with it than with SPL - although one of the reasons why I write this blog is to learn more so I don’t want to dump Splunk completely. I am not sure how I will be using the solutions, we shall see. As for Sentinel/Log Analytics, I used the parser for all Sysmon versions, available here. I saved the parser as a function with the name of Sysmon.

To the hunting: First, I tried to recognize the DLL:s that were often loaded by other processes. This being .NET, they are being loaded constantly by legitimate binaries but there were two DLL images which were loaded less than the others. These were “C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\clrjit.dll” and “C:\Windows\assembly\NativeImages_v4.0.30319_64\mscorlib\8d60a20bcb7b36d0ddf74b96d554c96e\mscorlib.ni.dll”, which both were loaded always by the AsyncRAT samples, but they were loaded by legitimate apps to0. I proceeded to join these two together:

Sysmon

| where EventID == 7

| where ImageLoaded endswith "mscorlib.ni.dll"

| join kind=inner (

Sysmon

| where EventID == 7

| where ImageLoaded endswith "clrjit.dll"

) on Image, Computer, ProcessId

| project Computer,TimeGenerated,Image, ImageLoaded, ImageLoaded1

I got quite a few results with this query as was to be expected. It does hit the malicious samples too, which is fairly important for threat hunting purposes. I proceeded to join the existing data to any DNS event or network connection generated by the same process. This did pickup the basic AsyncRAT samples, but was missing the first one which was acting differently.

Sysmon

| where EventID == 7

| where ImageLoaded endswith "mscorlib.ni.dll"

| join kind=inner (

Sysmon

| where EventID == 7

| where ImageLoaded endswith "clrjit.dll"

) on Image, Computer, ProcessId

| project Computer,TimeGenerated,Image, ImageLoaded, ImageLoaded1, ProcessId

| join kind=inner (

Sysmon

| where EventID == 22 or EventID == 3

) on Computer, Image, ProcessId

| project Computer, TimeGenerated, Image, RenderedDescription, DestinationIp, DestinationPort, QueryName, QueryResults

Unfortunately, with the first sample the process loading the DLL files is not actually launching the DNS query. The process which does launch the query is not loading any relevant DLL files to catch it, only AMSI and things like that. The same approach would not work in hunting the behavior by the first sample. I looked at the process creation event and noticed it was not logged, but the EvenId 10 (Process Access) was - this could be likely used. I created a query which joined the original two DLL loads, then joined that data to the Process Access event nd then finally joined it to the DNS query / network connection event similarly to the query above. This worked but also returned one false positive, so your mileage may vary. Developing in sandboxes is not providing realistic results but helps to develop stuff.

This starts to be quite heavy too. On my very light environment the query execution took ~minute. Might not be doable in a real environment.

Sysmon

| where EventID == 7

| where ImageLoaded endswith "mscorlib.ni.dll"

| join kind=inner (

Sysmon

| where EventID == 7

| where ImageLoaded endswith "clrjit.dll"

) on Image, Computer, ProcessId

| project Computer,TimeGenerated, SourceImage = Image, SourceProcessId = ProcessId

| join kind=inner (

Sysmon

| where EventID == 10

) on SourceImage, SourceProcessId, Computer

| project TimeGenerated, Computer, SourceImage, Image = TargetImage, ProcessId = TargetProcessId

| join kind=inner (

Sysmon

| where EventID == 22 or EventID == 3

) on Computer, Image, ProcessId

| project Computer, TimeGenerated, SourceImage, Image, RenderedDescription, DestinationIp, DestinationPort, QueryName, QueryResults

Here are the same queries for Splunk. I had issues with SPL when joining to the network event. This was because the subsearch limited to the default 50k limit, which I didn’t want to change - so take the queries with little grain of salt as I haven’t been able to fully test them out.

index=sysmon EventCode=7 ImageLoaded="*mscorlib.ni.dll"

| join type=inner Image, Computer, ProcessId [search index=sysmon EventCode=7 ImageLoaded="*clrjit.dll"]

index=sysmon EventCode=7 ImageLoaded="*mscorlib.ni.dll" | table _time, host, Image, ProcessId

| join type=inner ProcessId, host, Image [search index=sysmon EventCode=7 ImageLoaded="*clrjit.dll"]

| table _time, host, Image, ProcessId

| join type=inner Image host ProcessId [search index=sysmon EventCode=22 OR EventCode=3]

| table _time, host Image, TaskCategory, QueryName, QueryResult, DestinationIp, DestinationPort

index=sysmon EventCode=7 ImageLoaded="*mscorlib.ni.dll" | table _time, host, Image, ProcessId

| join type=inner ProcessId, host, Image [search index=sysmon EventCode=7 ImageLoaded="*clrjit.dll"]

| rename Image as SourceImage

| rename ProcessId as SourceProcessId

| table _time, host, SourceImage, SourceProcessId

| join type=inner host, SourceImage, SourceProcessId [search index=sysmon EventCode=10]

| rename TargetProcessId as ProcessId

| rename TargetImage as Image

| table _time, host, SourceImage, Image, ProcessId

| join type=inner host, Image, ProcessId [search index=sysmon (EventCode=22 OR EventCode=3)]

|table _time, host, SourceImage, Image, TaskCategory, QueryName, QueryResult, DestinationIp, DestinationPort

Conclusion

It was interesting to see couple of samples of the AsyncRAT to see how it looks like when executed. The tool/malware has quite some options that can be used (obfuscation, different kind of C2 comms etc.) so the queries developed are still quite targeted and would likely only catch small portion. They do also provide benign true positive but they are not intended for being really detection rules.

It was a lot of fun to analyze the sample(s) which proved to be a tad boring - although I sort of expected that. Hopefully I will figure out something else to write about next time than the malicious samples and hunting for them. This is all in good fun but I prefer variety. We shall see.

Thanks for reading!

HTML Smuggling - how does it look like?

HTML Smuggling - how does it look like?