Why Turla?

Lately I’ve done quite a lot of write-ups of testing currently active malware and how that could be potentially hunted for. I’d rather write about something else for a change, which led me to this topic. Turla has been in the news lately as their long running malware known as Snake was – well – dismantled by the US government. Turla was also raised to the news where I live which further raised my interest towards the group. Supo, which is Finnish Security and Intelligence Service, stated in the l0cal news that Turla has been active within Finland for years now.

What is Turla?

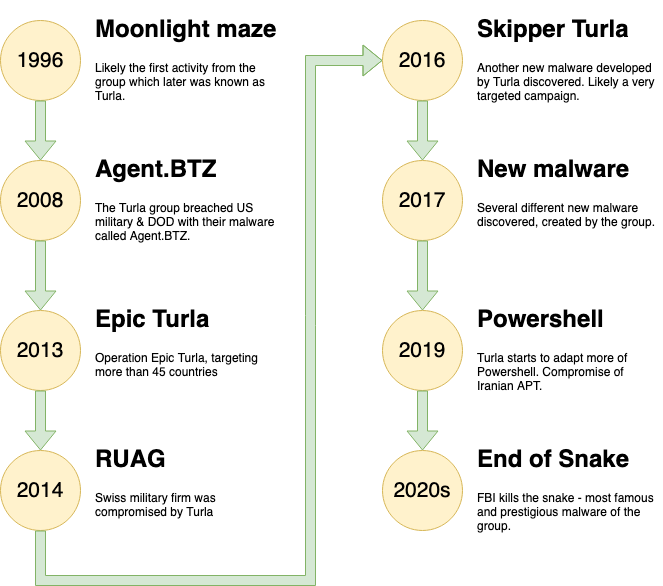

Turla is a Russian threat actor and an Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) group. The group has been operating for a long time and has been active at least since 2004 – but likely even longer than that. It is known with multiple other names as well, as is the custom with the APT groups. Some of the other names for the group include Venomous Bear, Uroburos and sometimes the group has also been called Snake. According to multiple articles they have been targeting more than 45 different countries and industries. As they are not a financially motivated actor their targets seem to be limited to industries which can hinder the governments ability to act or which can give valuable information to the Russian government. The group is sponsored by the Russian Federal Security Service, FSB.

Turla is known of using their own in house malware and utilizing a lot of watering hole an spear phishing attacks for gaining the initial access towards the victim organization. Some of their own malware include the Snake/Uroburos and TinyTurla. The first big thing I found by the Turla group was a malware known as Agent.BTZ which was discovered at 2008. This was a massive finding back in the 2008 and really made the Turla group known. However, while doing my research the first mentions I could find from the Turla group were from the year 1996. It is good to note that Turla is also a name of one of the malware which the group has developed. I am mostly referring to the group itself when using the term Turla within this blog post.

1996 – Moonlight Maze

While looking for information about Turla I came across articles about “Moonlight Maze”. It is one of the first cyber espionage groups which have been actively investigated by a group of researchers. Many of the researchers from different countries have found out that it is likely that the Moonlight Maze authors are the same as with Turla. It is highly likely that the Moonlight Maze is the earliest malware written by the Turla group. As Moonlight Maze was active in the 1990s it means that Turla has been active at least for 25+ years – just wow.

While looking for information about Turla I came across articles about “Moonlight Maze”. It is one of the first cyber espionage groups which have been actively investigated by a group of researchers. Many of the researchers from different countries have found out that it is likely that the Moonlight Maze authors are the same as with Turla. It is highly likely that the Moonlight Maze is the earliest malware written by the Turla group. As Moonlight Maze was active in the 1990s it means that Turla has been active at least for 25+ years – just wow.

Moonlight Maze was very advanced at the time, using multiple proxy servers to cover their tracks. The logs had survived from one of the attacks and have been analyzed by a team of researchers. These logs revealed that the group was using a backdoor built on the basis of LOKI2 tool. Similarly, Turla has been using backdoors built on the basis of the same tool later on.

Loki2 is a backdoor which was published on a Phrack Magazine in 1997. Rather interestingly, it works over ICMP which can make it effective even in 2020s. Quite often the defenders are focusing more on TCP/UDP which could mean that ICMP based communication is missed. It is still being used by some of the threat actors, although highly modified from the original.

Moonlight Maze was targeting the US military and government agencies. The group was targeting Solaris/*nix based system which is quite fascinating as nowadays the *nix platform is a rarer target for the threat actors. Initial access to the target systems were gained by exploiting a vulnerability on a web server, which was very easy to exploit. Basically, the threat actor could print out the *nix password file, gaining access through telnet with the legitimate credentials. Especially as the security monitoring capabilities in 1996 were in early stages these kind of attacks could easily go unnoticed. Not saying though that they wouldn’t now – I have been investigating plenty of cases where unauthenticated remote code execution vulnerabilities were used to gain access to a network.

After gaining access the group ran different tools to laterally move within the network and to steal information from the target devices. There is hugely interesting write-up available here if you’d like to learn more, especially about how the researchers were attributing MM to Turla. The next big thing where Turla has been attributed as the threat actor happened in 2008.

2008 – Agent.BTZ

In 2008, the Turla group used a malware known as Agent.BTZ to breach the US military computers. The malware was deployed on an infected USB drive to an army base, located in middle east. It is said that the threat actor left the infected USB drive to a parking lot of an army base after which it was connected to a laptop, however this story has not been verified of being true. Agent.BTZ was self-replicating and was able to spread overseas to the US, including the Department of Defense devices.

In 2008, the Turla group used a malware known as Agent.BTZ to breach the US military computers. The malware was deployed on an infected USB drive to an army base, located in middle east. It is said that the threat actor left the infected USB drive to a parking lot of an army base after which it was connected to a laptop, however this story has not been verified of being true. Agent.BTZ was self-replicating and was able to spread overseas to the US, including the Department of Defense devices.

This is quite interesting to me as just as late a in 2022 many companies were dealing with Raspberry Robin. This malware was similar to the Agent.BTZ infecting computers through infected USB drives. Both were also capable of infecting other drives connected to an infected device. It is quite interesting that similar tactics seem to work for the threat actors even 15 years later.

The Agent.BTZ was able to steal information and give a remote access channel to the Turla group. The old tricks have not changed much as the information stealer type of malware is currently by far the most popular malware-family, according to sandbox statistics. Interestingly the attack led the DOD to ban the USB drive usage – which was hindering the US army operations as the personnel were used to using USB drives to store information. Cleaning the infection took more than a year and even after that the officials were unsure if they were unable to clean all the infections. The military networks were clean, however it was noted that the DOD networks might still have infected machines in them, after more than a year of the initial infection.

Agent.BTZ was capable of infecting all the removable drives which were connected to an infected device. This was done by copying a malicious autorun.inf file to the drive with instructions to launch the file. When the drive would be connected to a clean device it would automatically run the malicious code. This attack vector has been fixed in Windows years ago but rather interestingly the malicious payload was launched by running the following command: rundll32.exe .\\[random_name].dll,InstallM. This to me personally is very interesting as I have been hunting for malicious code being loaded by rundll32.exe for years now. It seems that this technique is very old, having been active for at least 15 years. The difference is that back then it was utilized by the highly skilled APT groups, now it can be utilized by all the bad actors.

The malware would then download a malicious DLL image file which would be loaded and malicious remote thread would be created to the Internet Explorer process. This was done to bypass potential firewalls. A very good write-up is available here.

2013 – Breach of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Finland

The activity in 2013 was very interesting to us Finns. It was reported in the local MTV news that the Ministry for Foreign Affairs have been compromised. It is possible that the threat actor have been inside the network for as long as 4 years. It is good to note that the attack potentially allowed for the threat actor to gain access to the European Union data using the servers located in Finland. The Finnish officials got a tip from the overseas of the potential compromise.

When the investigation started it was discovered that the malware used was potentially Red October. However, later it was stated that Red October was found from a single device but it was not the main tactic used by the threat actor. Unfortunately, I was not able to find much more details of the case.

One of the reasons why the Red October has been associated to Turla group is that it shares a lot of similarities to Agent.BTZ. Both of the malware have similarities to the Turla malware which is used by the threat actor later on. It is likely that the Agent.BTZ was the starting point, after which the Red October was developed which led to the development of Turla malware. The Red October malware was mainly trying to steal information of the target network, fitting the cyber espionage scheme very well. Red October had more than 60 C&C domains and they started to shutdown the C2 infrastructure after the Red October malware was discovered.

Epic Turla

The second major activity in 2013 was the operation “Epic Turla”. Kaspersky wrote an article about Epic Turla in 2014 which they had been analyzing for 10 months before releasing the article. Kaspersky stated that hundreds of computers had been infected in more than 45 countries during the operation. The threat actor was mostly targeting government agencies, research and pharmaceutical companies. The threat actors was using at least two different zero-day exploits in the campaign.

The second major activity in 2013 was the operation “Epic Turla”. Kaspersky wrote an article about Epic Turla in 2014 which they had been analyzing for 10 months before releasing the article. Kaspersky stated that hundreds of computers had been infected in more than 45 countries during the operation. The threat actor was mostly targeting government agencies, research and pharmaceutical companies. The threat actors was using at least two different zero-day exploits in the campaign.

The Turla group was using a sophisticated multi-stage attack, beginning with the Epic Turla but it could potentially migrate to their other tooling like the Carbon backdoor. Sometimes there might be multiple backdoor present on a single machine – if one would be detected and removed the other would remain active. They would deploy rootkit as the persistence mechanism, one likely candidate being the Uroburos/Snake rootkit.

From cyberspace to the actual space: One of the cool and to me mind blowing thing about the activity of the Turla and other APT groups is the use of satellite connection to their C2 infrastructure. Reportedly the APT groups started to use the satellite connections somewhere around 2007, albeit it used to be very rare at the time. Turla is one of the groups which have used the satellite connections in their operations. The benefit of the satellite connection is that it is hard to pinpoint where the actual server is located. It makes it hard to pinpoint the attack to a group. The receivers can be anywhere in the area covered by the satellite, making it very hard to find the actual device. The originating IP could also be pretty much anywhere in the world.

The satellite connections used to be very expensive. However, Turla and the other groups didn’t really want to pay the price (it would also have an operational risk to the group). The threat actors used the downstream-only internet access which is unencrypted with DVB-s card to hijack the internet connection. The attackers satellite antenna would be pointed to the same satellite with a legitimate connection by some other company and it would listen on the packets from the internet to a specific IP. When a packet would be identified a spoofed reply packet would be sent towards the satellite. It would abuse the fact that the packets to the closed ports would be dropped – instead of sending RST or FIN packet.

It is possible that the Epic Turla operation was also using the Satellites in communicating towards the C2 servers.

The initial access tactics which the group was using was based on Spearhishing and watering hole attacks. The Spearphishing included weaponized PDF attachments which were exploiting two different vulnerabilities on the PDF readers. The watering hole attack was using Java, Flash and Internet Explorer exploits. The naming convention in the attachment sent was pointing to NATO, Geneva conference and security protocol amongst other things. It was reported that the attacks were very dynamic, using different methods depending on the availability of the vulnerabilities. The C2 communications were also proxied through several layers which has been a tactic utilized by the group since the start of the operations.

2014 – Breach of the Swiss military firm RUAG

The earliest signs of the Turla being able to breach RUAG are from 2014. However, the report released by the company state that even though the first signs are from 2014 it is not know when they were initially compromised. The proxy logs were not available before September 2014. A quote from their report which I absolutely agree to:

We would like to emphasize that public blaming is never appropriate after such attacks. These attacks may happen to every organization regardless of their security level. What is much more important is to learn from these attacks and to raise the bar for the next time the attacker tries to infiltrate the network.

The victim should not be blamed for the attacks. It was not the victims fault that they got attacked – the blame should be on the criminals who were attacking the company. Even if the company is well protected the APT level actors are likely to find a way in to the network – if they want to. This is not to say that there shouldn’t be consequences if even the basic security measures are ignored by the companies.

The first signs of the compromise were found in December 2015, however it was noted that the data was limited and in-depth investigation is not possible. On January 2016 the incident was escalated to a major incident. The investigation lasted for several months but the initial phase was ending at the end of January. After that the investigation continued and new C&C servers were being discovered. The monitoring was improved and it was continued to be improved until the end of April 2016. There were several press reports released on 3.5.2016 and according to the report it was damaging the investigation and hindering some of the monitoring to useless.

Interestingly, it seems that there were still references to the LOKI2 in the Snake tool which the defenders were analyzing. Remember, the LOKI2 tool was released in 1997, 17 years before of this compromise. The malware is injecting only to common processes known to connect to the internet, likely to fool the local firewall which could block the traffic based on the process name. The persistence was achieved with a Service or a rootkit. Lateral movement was done with named pipes, psexec and WMI. When the threat actor had no use for a particular device anymore, they were removing their own malicious code from the device.

At the end of 2014 it was also reported that as opposed as what was believed the Turla had capabilities of attacking other operating systems than Windows. It was reported that the Malware used by Turla had also Linux modules. To me this isn’t really a big surprise at this stage given the history of the APT group. The operations by the group were started with *nix based malware. The latest capabilities added were using public sources, with the backdoor being based on a backdoor called cd00r.

2016 – Skipper Turla

The Skipper Turla was another version of the malware created by the Turla group. It was using a newly developed JavaScript payload and shared similarities with older payloads created by the group. The java script payload at this time was developed to avoid detection. It was also running in parallel with other Turla operations and the researchers believed that this was a specific, targeted campaign. The campaign included the usage of the hijacked satellite connections which were described earlier.

The Skipper Turla was another version of the malware created by the Turla group. It was using a newly developed JavaScript payload and shared similarities with older payloads created by the group. The java script payload at this time was developed to avoid detection. It was also running in parallel with other Turla operations and the researchers believed that this was a specific, targeted campaign. The campaign included the usage of the hijacked satellite connections which were described earlier.

The Skipper Turla campaign was focused on targeting embassies and consular operations. It was also shifted targeting additional targets later in 2017. The delivered payload was digitally signed on most of the occasions with the certificate pointing to a company called “Solid Loop Ltd.”. This was likely a front organization to acquire the certificates for illegitimate purposes. The campaign was relatively short lived and it diminished in June 2017.

2017 – The most active year yet

The APT group was very active in 2017 – or maybe the detection capabilities got better so that their activity was detected better. There was huge amount of activity during the 2017. The group was developing their arsenal by building new malware and improving the older tooling. One reason for this activity likely is that some of their tooling had “burnt”. This means that the defenders could potentially detect the usage of the tools and thus the group might feel like that they need to develop new versions. This likely is true as they are targeting high value targets which often are defended better than the average companies. The Turla group is also known to drop their burnt tooling and create a new version.

There was a new version of the tool Carbon, which is one of the many backdoors that the group has created. This was one of the tools which were used in the attack against RUAG. Swiss GovCERT.ch had analyzed the version of the Carbon which was used in the attack. They published a research document about the attack and thus the tool was recognized by the public. It had similarities to Uroboros rootkit and could be seen as a lite version of the Uroboros.

The group had developed another tool. This time they were using a tool called Gazer, which is yet another backdoor. The malware was spotted from the European embassy and ministry systems. The malware received encrypted commands and it can launch the commands either locally or it can target remote devices. The malware uses virtual file system in device registry to avoid being detected.

The Snake malware was also being ported to the OS X. The Mac version of the malware was delivered as a fake Adobe Flash installer and it was digitally signed with Apple developer certificate. The certificate was revoked by Apple but it is likely that the Turla group was not really affected by this. The group is so resourceful that they likely did quickly discover another way.

They were also targeting the G20 task force participants. To do so they had developed yet another tool – this time it was a .NET based dropper. This was likely delivered to the participants but also to other parties interested in the event. They also had updated many of their other malware during 2017. It should also be noted that the group was using more generic tools. They had initiated the operation Mosquito Turla in which Metasploit was used before dropping the groups own malware. This is quite interesting as normally it seems that they are more found in using their own stuff.

The most vicious act of the group in 2017 was to use Britney Spears’ Instagram account to point their malware to the C2 server. The group was commenting on a picture posted by the POP star which contained a hidden link to find the C2 server address. Amazing tactic to avoid being detected with the normal means, as the implant would connect to Instagram instead of the actual C2 address. I officially continue to be amazed.

2019 – Powershell and Iranian APTs

The group had already used Powershell before, the Posh-SecModule for example. It had it’s fair share of problems which is why the Turla group likely developed their own improved versions of the Powershell tooling. The Powershell loader created by the group used two different persistence methods, one being the Powershell profiles and the second one was WMI based persistence. The malware was capable of bypassing AMSI, using the technique presented in Black Hat Asia 2018.

The group had already used Powershell before, the Posh-SecModule for example. It had it’s fair share of problems which is why the Turla group likely developed their own improved versions of the Powershell tooling. The Powershell loader created by the group used two different persistence methods, one being the Powershell profiles and the second one was WMI based persistence. The malware was capable of bypassing AMSI, using the technique presented in Black Hat Asia 2018.

They were using a Powershell backdoor known as Powerstallion. This is a backdoor which received it’s command through Onedrive or other cloud storage instead of an actual C2 server. This was quite early usage of this technique, during 2022 the threat actors were reported of increasingly using similar techniques. This is hard to detect as the beacons are connecting to a legitimate cloud service.

The Powershell malware contained the option for RPC backdoor. This would work in a client-server manner so that the threat actor could give out commands to the clients using the central server. This central server likely was one of the initially accessed devices from which the threat actor was laterally moving to other devices within the internal network.

The Turla group was able to compromise the infrastructure of Iranian APT group. Apparently the Turla group used compromised credentials to access the infrastructure. While at it Turla stole some of the tools which the Iranian group had developed. Using the gained access they gained access to different systems in Middle East.

2020s

The same trends continue in 2020s. The group is developing it’s own capabilities sometimes loaning from the public sources.

At the end of 2020 there was a huge breach against SolarWinds. This is a company offering system management tools and it is being widely used by different organizations. SolarWinds are offering their services to major companies, including Fortune 500 companies and US government agencies. The hack was targeting one of the tools of the company known as SolarWinds Orion. The threat actor was able to infiltrate the SolarWinds environment injecting a backdoor to the Orion which was then pushed to the customer environments. This was a Supply Chain attack. The result was that most of the companies utilizing the Orion software were updating their software to a version which included a backdoor, giving access to the attacker.

The threat actor gained access to the SolarWinds networks in 2019 after which they had developed custom code and injected it into the Orion. The malicious code was called Sunburst. The malicious update delivery started in March 2020. The attack has been attributed by many researchers towards Russian government sponsored hackers. It is still unclear which group was behind the attack. However, it is clear that the backdoor was sharing some of it’s features with one of the tools developed by the Turla group, Kazuar. The similarities with the Sunburst and Kazuar included couple of different algorithms and the extensive usage of the FNV-1a hash. It is possible that the Turla group was heavily involved in the Sunburst attack, however the similarities in the code are not proving that to be the case. It is possible that the malware developers would have, for example, sold similar malware to different entities.

In 2022 the Turla group registered C2 domains of commodity Malware Andromeda. The C2 domains were expired, likely because it is very old piece of Malware. The malware used to be active in the early 2010s and had been a minor threat recently. The malware was delivered through infected USB drive and in this occasion the malware infected a device in Ukraine. The Turla group gained access to the device by registering the C2 domains and then pushing their own malware through the C2 connection. After infecting the device with their own malware the normal operations continued by the group. It is very likely that the Turla group has been targeting their efforts towards Ukraine as of late as Russia is attacking the country.

It was announced in June 2022 that Turla group would be used as the basis of the next round of the Mitre Engenuity evaluation. This is Mitre’s own evaluation of the endpoint security tooling on which they give no scores to the products. To make the data useful you need to analyze the actual results. It is possible to look at the stats generated by others but these are quite often published by the tool vendors and they are trying to find a suitable angle to highlight their own product. This is all fair but to take full advantage of the hard word at Mitre you probably want to analyze the results yourself.

The latest news are part of the reason why I started to write this post: FBI announced that they were able to dismantle the Snake malware. This malware is one of the oldest and fanciest tools in the arsenal of the group. This is the rootkit, also known as Uroburos – a snake eating it’s own tail. FBI developed a tool called Perseus to battle the Uroburos. The creation was started by creating a tool which was capable of detecting the network traffic by the Uroburos tool. FBI was able to pinpoint 8 infected devices within United States – asked permission to remotely access the devices – and then monitored the malware for years. They were able to detect other victims and to impersonate the Turla group. They were also able to give commands to the Snake malware. Then with the court permission they gave a destructive command to the malware which overwrote the vital parts of the malware, removing it and also hindering the Turla group in-able to access the implants anymore.

The Turla group is known of using backup backdoors and the FBI was only targeting the Snake so it is possible, or even likely, that the threat actor still has access to the devices. At least some of them. Still, I find this extremely impressive. A great ending for the story too.

Threat hunting the APT groups

I am not sure what to write here. The tactics of the group have been so sophisticated that it is hard to think of what to hunt for. The tactics that the group use are ever changing and if their tooling gets burned they develop a new one. I do also think that most of the defenders do not face APT groups very often, if ever. Nevertheless, the modern financially motivated groups use similar tactics and I think that the gap between of the APT groups and other actors isn’t as big as it used to be. There have been more and more news where the APT groups have actually used a public PoC code to exploit commonly known vulnerabilities too.

This time I will not create any queries, rather I add some ideas which I have that can be turned into hunting rules. General ideas, more or less.

- While going through the historical articles there have been some similarities with the malware developed by Turla. For example, they were running similar discovery commands. These commands could be used as the basis of a rule – hunt for the commands being launched in a short interval. I wrote a blog post of this subject before (Running multiple instances of discovery commands in short period of time – Threat hunting with hints of incident response) but do keep in mind that this is not useful out of the box. It needs a lot of tuning. It can provide some insight how this kind of hunt can be done.

- Rundll32/regsvr32 based hunting. These were some of the techniques which were present with many of the attacks launched by the Turla group. They are used a lot by the financial groups and as such they are amazing target for threat hunting or detection rules.

- Hunting for C2 communication towards known cloud services. During the investigation I noted that the Turla group used Instagram, Onedrive and other cloud storage options for giving out commands to the malware. Hunting for abnormal connections towards these can prove to be valuable.

- ICMP based C2 connections. The Turla group has utilized ICMP based connections since the start – they started this already in 1996 with the malware based on the Loki2 tool and apparently they have been utilizing similar backdoor even in the 2020s.

- Hunting for 0days can be quite hard as you don’t really know what you are looking for. However hunting for recently (in the past 6 months) released exploits is possible and advisable. I have to say though that the older vulnerabilities are actually used a lot more than the recent ones. It can prove to be valuable to hunt for exploiting the older major vulnerabilities especially if you know that for some reason they have not been patched.

- As stated hunting for 0day exploits can be hard. One idea to tackle this would be to hunt for rare processes spawning processes often utilized by the threat actors. These processes could include cmd.exe, powershell.exe, rundll32.exe, regsvr32.exe and many many others. This can be a little hard and requires baselining the processes which are normally launching these processes in your environment though.

- Notice the absence of Persistence techniques? I love hunting for persistence and Turla did use service based persistence with some of it’s malware. That can be hunted. However, they also did use a lot of rootkits. I do not really know how you would threat hunt rootkits with endpoint based solutions.

Conclusion

This post has been fun to write. I’ve dwell deep into the history of the Turla group, hopefully bringing a high-level histogram of the group in enjoyable format for the reader. I learned a ton of the history of the group and was absolutely amazed of the techniques that the APT group has been using during the years of being active. The ability to adapt to the situation and willingness to ditch burned infrastructure is jaw dropping. In reality most of my work has been done against the financially motivated actors which are not acting usually with much any finesse so this is just next level. I knew that APT groups do have much more sophisticated means to attack but this was eye opening research towards the Turla group and APT in general.

The data which I’ve gone through has also emphasized it once more how little I know. The amazing articles, write-ups, malware analysis and case reports from truly talented people is just mind blowing. It has been a great pleasure to go through the material, albeit I have had sometimes issues in understanding especially the highly complex reverse engineering reports.

The post is based on highly valuated work of others. All the resources from which I have gathered information are added below. The write-up includes the events which I found particularly interesting but could miss some major activity by the Turla group. I did use quite a lot of time to do my research towards the group but it is likely that I have missed many things which could be included.

References

In no particular order.

- https://www.industrialcybersecuritypulse.com/threats-vulnerabilities/throwback-attack-russian-apt-group-turla-has-hit-45-countries-since-2004/

- https://attack.mitre.org/groups/G0010/

- https://securelist.com/the-epic-turla-operation/65545/

- https://exatrack.com/public/Tricephalic_Hellkeeper.pdf

- https://www.welivesecurity.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/ESET_Turla_ComRAT.pdf

- https://www.cfr.org/cyber-operations/agentbtz

- https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2008-nov-28-na-cyberattack28-story.html

- https://paper.bobylive.com/Security/APT_Report/A_Threat_Actor_Encyclopedia.pdf

- https://www.kaspersky.com/blog/moonlight-maze-the-lessons/6713/

- https://dmfrsecurity.com/2022/01/15/100-days-of-yara-day-27-loki2/

- http://phrack.org/issues/49/6.html

- http://phrack.org/issues/51/6.html

- https://securelist.com/penquins-moonlit-maze/77883/

- https://securelist.com/agent-btz-a-source-of-inspiration/58551/

- http://blog.threatexpert.com/2008/11/agentbtz-threat-that-hit-pentagon.html

- https://www.mtvuutiset.fi/artikkeli/mtv3-suomen-ulkoministerio-laajan-verkkovakoilun-kohteena-vuosia/2369718

- https://securelist.com/satellite-turla-apt-command-and-control-in-the-sky/72081/

- https://media.kasperskycontenthub.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/43/2014/08/20082353/GData_Uroburos_RedPaper_EN_v1.pdf

- https://www.govcert.ch/downloads/whitepapers/Report_Ruag-Espionage-Case.pdf

- https://www.telsy.com/following-the-turlas-skipper-over-the-ocean-of-cyber-operations/

- https://yle.fi/a/3-8591548

- https://www.welivesecurity.com/2017/03/30/carbon-paper-peering-turlas-second-stage-backdoor/

- https://cyberscoop.com/gazer-backdoor-turla-eset-2017/

- https://blogs.blackberry.com/en/2017/06/this-week-in-security-6-09-2017

- https://www.proofpoint.com/us/threat-insight/post/turla-apt-actor-refreshes-kopiluwak-javascript-backdoor-use-g20-themed-attack

- https://www.welivesecurity.com/2018/05/22/turla-mosquito-shift-towards-generic-tools/

- https://www.welivesecurity.com/2019/05/29/turla-powershell-usage/

- https://www.theregister.com/2019/10/21/british_spies_russia_faking_iranian_hack/

- https://www.mandiant.com/resources/blog/turla-galaxy-opportunity

- https://techcrunch.com/2023/05/10/turla-snake-malware-network-russia-fsb/

- https://securelist.com/sunburst-backdoor-kazuar/99981/